WEBサイトに掲載している文章及び画像の無断での転用や転載はご遠慮ください.

講演内容の書き起こし:本堂

講演「科学の不定性と裁判:科学者の視点から」

Presentation “Scientific incertitude in law court: From a scientist’s point of view”

講師:本堂 毅(東北大学理学研究科准教授)

Tsuyoshi Hondo (Associate Professor, Graduate School of Sciences, Tohoku University)

スライドのPDF

あいさつ

(司会)

それでは定刻となりましたので、国際シンポジウム「科学の不定性と社会〜いま、法廷では・・・」を開催いたします。最初に東北大学理学研究科教授本堂毅より、当シンポジウムの狙いをお話しします。

Moderator: It’s time to start the International Symposium, “Scientific Incertitude and Society: Lessons from Law Court.” First Professor Tsuyoshi Hondo will explain the aims of this symposium.

(本堂)

おはようございます。東北大学の本堂です。このシンポジウムの組織委員長を務めており、今日の最初の講演では、このシンポジウムの趣旨と合わせて私の発表を行いたいと思います。

朝早いですので、最初は少しゆっくりと、皆さんご存じかもしれないことをちょっと復習しながらというか、一緒に考えながらお話しさせていただければと思います(以下、スライド併用)。

Hondo: Good morning. I am Hondo from Tohoku University. I am chairman of the organizing committee for this symposium. I would like to explain the main purport of this symposium and give the opening presentation. It’s still early in the morning, so let’s start rather slowly, reviewing some facts that you may already know. I hope this will be an opportunity for us to think together about scientific incertitude and society. (The following is presented using slides)

♦page 2

私の発表のタイトルは「科学の不定性と裁判:科学者の視点から」というものです。 今回は法律が関係する、特に法廷が関係するお話が、このシンポジウムの大きなテーマですが、私は法律家ではありません。法律家ではない私がなぜこういうお話をするのかを含めて、今から40分ほどお話をさせていただきます。

The title of my presentation is “Scientific incertitude in law court: From a scientist’s viewpoint.” Issues related to laws, law courts in particular, are the main themes of today’s symposium, but I am not a lawyer. Well then, why do I talk about these things though I’m not a lawyer. That’ll be one of the things I will be explaining during the next 40 minutes or so.

♦page 3

皆さんご存じのように、昨年の3月11日に大震災が起こりました。私は東北大学におり、それほど大きな被害ではありませんでしたが、私も震災の被災者です。1年半ほど自分の研究室もないという状態におかれるなどいろいろ大変なことがありました。

今回私たち、このJSTのRISTEXというプロジェクトでこのシンポジウムを開催しておりますが、今回の3.11のあと、科学者がさまざまな発言をしていました。その科学者の発言、いわゆる科学的助言というものの扱い方、社会の中での生かし方をずっと見ていて、大変忸怩たる思いがありました。

その非常に代表的なフレーズとして、「ただちに影響はない」というものがよく使われていましたが、今日今からお話しすることはこのフレーズに代表されるような科学と社会の間での行き違いや社会的な不信、科学と社会が、

そういうことがどこから起こってくるのか、そういうことを一緒に、このシンポジウム全体を通して考えてみたいと思っています。

As you may all know very well, a devastating earthquake disaster struck Japan on March 11th, last year. At that time I was in the campus of Tohoku University. Although I did not personally experience a great damage, I was also a victim of the disaster. I was unable to use my laboratory for about a year and a half, and there were many other things that I had to cope with due to the disaster.

Today, this symposium is being held as a project by JST-RISTEX (Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society, Japan Science and Technology Agency). After the 3.11 disaster, many scientists appeared in the media making various comments on various relevant issues. I was carefully watching these comments and how these “expert advices” were being treated in society. I felt deeply embarrassed about it all.

One of the representative “scientist phrases” frequently heard was “no immediate effect.” This phrase kind of symbolizes the misunderstandings between science and society, or social distrust in science. Today, through this symposium and together with you all, I’d like to look into why such misunderstandings occur.

♦page 4

今お話ししたように、このシンポジウムで考えたいことは、科学と社会のボタンの掛け違いを、その原因を探るということです。つまり震災の前後で、福島の原発の事故もありましたが、もちろん責任のある方というのはいて、犯人探しのようなことをやることに意味がないというわけではありませんが、しかし社会とその社会の中での科学との間にさまざまな誤解があって、その誤解の下に制度が作られてきているという現実もまたあります。それであればその誤解を解きほぐすところから行わなければその問題の根本的な解決にはならず、また同じような問題が繰り返されるというのが私たちの認識です。

そのための一つのキーワードとして、今日お話しいただけるスターリング教授が先駆的に研究していた「科学の不定性」という概念が、私たちは大変大事なものだと思っています。そしてスターリング教授の研究というのは理論的な研究ですが、ただ理論のお話だけではなく、実際にどういうふうに社会の中で科学を生かしていけばいいかということを考えるためには、実践、実際にどういうことをやればいいかを考えることが大事です。 その非常に優れた実践例の一つとして、オーストラリアのマクレラン判事をお呼びして、コンカレントエヴィデンスの話をしていただくということになっています。

As I just mentioned, what I want to achieve through this symposium is to clarify the root cause of the misunderstandings between science and society. With regard to the earthquake disaster and the subsequent accident at Fukushima Nuclear Plant, naturally, there are people who are responsible of certain aspects of the disaster. So, I’m not saying that there’s no point in trying to identify the responsible person, but it’s also true that the entire system is built on misunderstandings, various misunderstandings between science and society. If so, then we must start from resolving the misunderstandings so as to be able to reach a fundamental solution. Or else, we will repeat the same mistakes again.

We think that one of the key words for resolving the misunderstandings is “scientific incertitude,” a concept pioneered by Professor Andrew Stirling, who will also be speaking today. Professor Stirling studies the theoretical side, but to actually make use of science in society, it is also important to examine the practical side, in other words, what we should actually do in practice.

As one great example of good practice, we have invited Justice Peter McClellan from Australia to give us a speech on concurrent evidence.

♦page 5

皆さんご存じのように、地球温暖化という問題があります。少なくとも私は、この地球温暖化の中に、科学と社会の間のいわゆるボタンの掛け違いの典型的な例があると思っています。例えば新聞やテレビをご覧になったりすると、こういう記事がよく出てくると思います。「温室効果ガスによる温暖化は科学的証明がなされていない」。したがって科学的証明がなされていないのに温室効果ガスの削減などの対策を行うのは非科学的である。けしからん、というような意見が、少なからずあると思います。

As you all know, we are facing the problem of global warming. I personally believe that this global warming is a typical example of misunderstandings between science and society. For example, I’m sure you have seen or heard in newspapers or TV that “It has not yet been scientifically proven that green house gases (GHG) cause global warming,” and therefore, to take measures for reducing GHG when the phenomenon hasn’t even been scientifically proved is unscientific and non-sense. Not a few people have this kind of opinion.

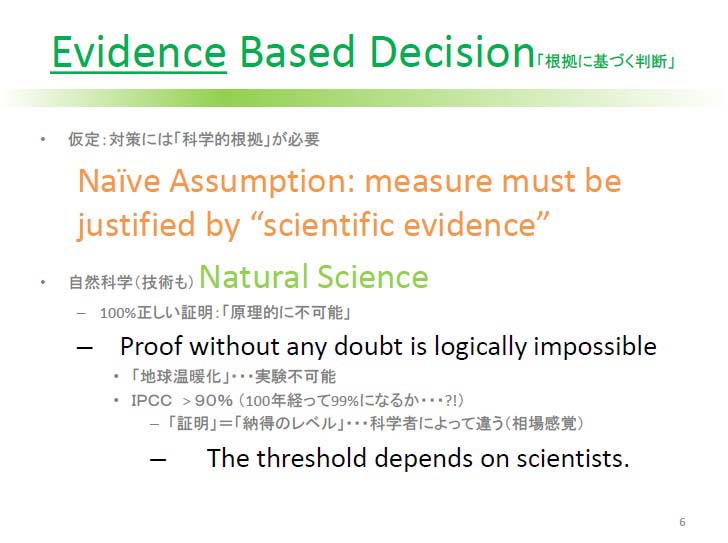

♦page 6

そのときのこの意見の前提に何があるかを考えると、対策には科学的な根拠が必要であるという、暗黙の仮定がおかれています。しかし自然科学というものがどういうものかということを考えると、100%正しい証明というものは原理的に不可能なことです。もちろん教科書に載っているような、ほぼ確実に正しい知識というものはありますが、地球温暖化のような現象というのは、実験することができません。地球と太陽と、みんな実験室に作って実験するというようなことは当然できないわけです。したがってIPCCが言っていることも、せいぜい90%程度以上で、温室効果ガスによる地球温暖化が正しいであろうと言っているわけです。もちろんIPCCの言っていることがどれほど正しいかということ自身にさまざまな議論がありますが、例えばIPCCがこれから100年研究をして、90%の確率が99%になるかどうかも怪しいというか、分からない、保証は全然ありません。それが科学というものの現実です。そしてまたどこまでその確率が高まったら証明になるかというものは、科学の世界の中でそのような定義はありません。つまり証明というのは結局のところ納得のレベルであって、科学者によって異なります。ある科学者は、これが証明されたと思い、ある科学者は証明されないと思うということが当然起こりますし、99%になっても、1%は正しくないとしたら、それは証明ではないという人がいるかもしれません。それが科学というものの現実です。

When we look at this opinion, we see that the argument stands on the implicit assumption that scientific basis is a prerequisite for implementing countermeasures. Considering the nature of natural science, however, it is logically impossible to proof something 100% correctly without any doubt. Of course, there is some knowledge, like those written in textbooks, that we know are almost certainly true. But we cannot experiment and prove a phenomenon like global warming. We can’t create an Earth, a Sun and the atmosphere in a laboratory to experiment global warming. Therefore, what IPCC is saying is of 90% probability or so. They’re only saying that green house gases are probably causing global warming. There are also a lot of arguments going on as to how accurate IPCC’s announcements are, but I doubt that even if IPCC continued studying the matter for 100 years more, the probability rate would rise from 90% to 99%. There’s no guarantee to it, and that’s the reality of science. How high does the probability rate need to be in order that something is considered “proved”? No such threshold has been defined in science. In other words, “proved” points to a level of conviction, a level that varies by each scientist. While some scientists consider one thing to be “proved,” other scientists don’t. There may be people that won’t accept something to be proved when 1% is incorrect, even if the probability was 99%. And that is also the reality of science.

♦page 7

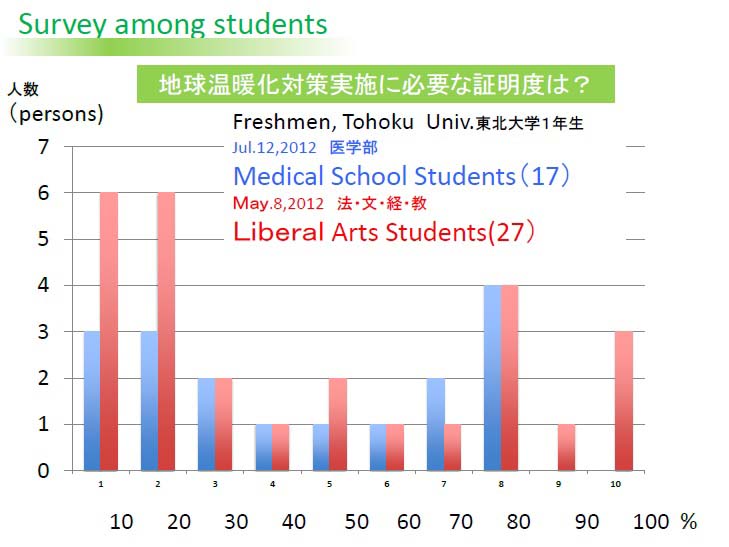

私は東北大学で、文化系、理科系両方の学生、1年生に対して、実験を通した授業を長年続けています。学生たちに対してアンケートをとると、地球温暖化に対してよくアンケートをとるのですが、例えば何%になったら温暖化の対策をとるべきでしょうというような質問を投げかけるわけです。一斉に、まったく同じときにまったく同じ質問をすると、このように分布が非常に大きく分かれます。これを見て学生たちは非常に驚くのです。まったく同じ場でまったく同じ学年で同じ質問がされても、これだけ意見というのは分かれるということです。 赤い方は文化系の学生で、青い方は医学部の学生ですが、どの学部でやってもこのように分かれます。

For many years, I have been teaching laboratory works to freshmen both from human arts and science courses in Tohoku University. I often carry out a questionnaire survey of the students, and one question I often ask is “At what probability rate should we start taking countermeasures against global warming?” I concurrently ask all the students exactly the same question, but their answers are widely distributed as shown in the chart. When the students see these results, they are struck by the wide difference in opinion, despite students of the same grade year were asked the same question in the same situation.

The red bars show the answers of students from human arts courses and the blue bars medical students. No matter what faculty the students belong the results are always widely distributed like this.

♦page 8

あるいはロシアンルーレットというものがあります。これは何かというと、ピストルのシリンダーに1発だけ弾を入れて、それを回して顔に向けて引き金を引くという、よく映画などで出てくるような、そういうゲームです。これは、弾が発射される確率は、はっきり分かっていて、6分の1です。つまり17%です。確率としてはこれはいわゆる蓋然性というようなものはないかもしれません。17%です。でもこれをやってみようと思う人は、多分この会場の中にもほとんどいないと思うのです。17%でも嫌だ、やらないという判断が当然あるし、それは普通でしょう。

I think you have ever heard of a Russian Roulette. Russian Roulette is a game, in which a revolver gun is loaded with just one bullet, then the cylinder is rotated randomly. The gun is pointed to someone’s face and the trigger pulled. Perhaps you’ve seen it in a movie. The probability of being shot is one sixth. That is, approximately 17%. This is not so highly probable, but I don’t think there is many here in this room who wants to try this game. Most people wouldn’t want to risk their lives even for a 17% probability, and that’s a matter of course and normal.

♦9

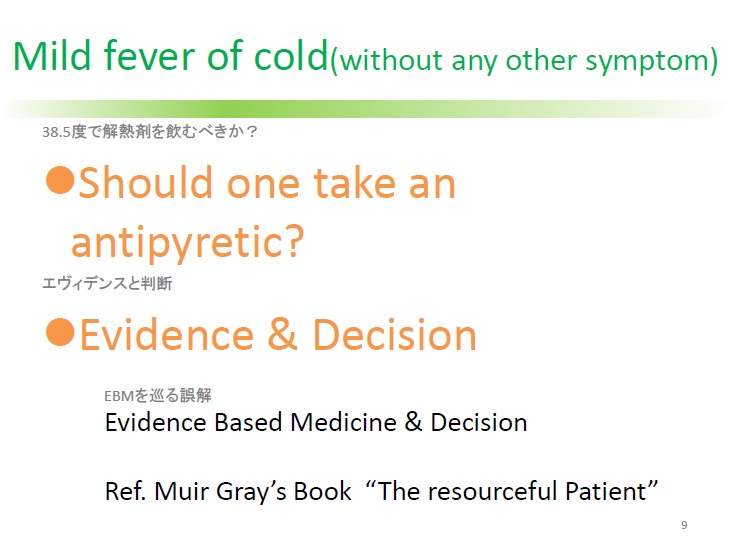

あるいは、風邪で微熱が出る。これもよく学生さんと議論するのですが、38度5分で解熱剤を飲むでしょうかと、学生さんに質問します。これは学部によってだいぶレスポンスが、反応が違うのですが、医学部の学生にこの質問を出すと、これはもう、ずっと何年もそうなのですが、90%の学生が、解熱剤を飲むべきだと言います。当然これは医学に通じている方ならご存じでしょうけれども、解熱剤を飲ませるとむしろ治癒が遅くなる、あるいは悪化する率が上がるということが、医学的なエヴィデンスです。この話を学生たちにすると、今度は、「いや、解熱剤は飲まない方がいい」と言います。その次に、では今度は、今日、午後に医師の国家試験がある、どうしますかと聞くと、やはり飲みたいと言います。つまりここで分かることは、エヴィデンスと判断というものは違うものだということです。もちろん判断にエヴィデンスを使うし、それを使うことは非常に良いことですが、でもこの二つは全然違うものだということが、ここで分かります。

よくEvidence Based medicineという、科学的根拠に基づく医学というものが言われていますが、今お話ししたような、科学で判断が決まるというような考えが結構日本にはありますが、そういうものがかなり大きな間違いを、ミスリーディングというか、誤った考えだということは、そのEvidence Based medicineを作ったイギリスのMuir Grayという人の本にはっきり書いてあることです。

Let’s think of another example. Let’s say you have fever from a cold. Do you think you should take antipyretics when your fever is 38.5 degrees C? This is another question I often ask my students. Students respond quite differently to this question depending on the course the student is taking. When I ask this question to medical students, 90% of the students reply that they will take antipyretics. This trend has not changed for years. Those who are familiar with medicine, however, know that medical evidence show that the use of antipyretics tends to hinder natural recovery or even raise the probability of worsening the cold. When I tell this to my students, they start saying “Perhaps I shouldn’t take antipyretics.” Next, I ask them, “But what if you have to take the national exam for medical practitioners on that day?” Then, they answer they want to take the antipyretics. What we can see here is that decision is not always based on evidence. Of course, people use scientific evidence in their decision making, and it’s a good practice, but here we can see the evidence and the decision are two completely different things.

We often hear the term “Evidence Based Medicine.” As I just told you, the idea that decision making should be based on scientific evidence is prevalent in Japan, but that’s not always the case. Muir Gray, the very person who coined the term “Evidence Based Medicine” clearly states in his book that it is a misleading idea to think that all decisions are or should be based on scientific evidence.

♦10

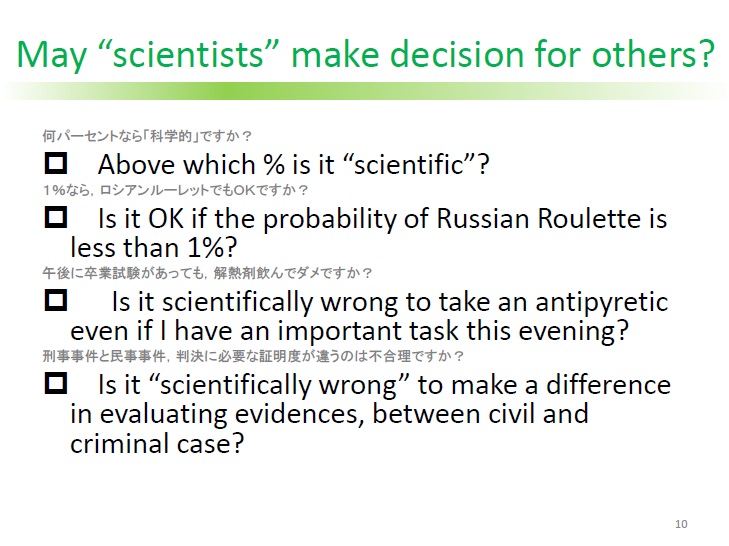

今お話ししたことを少し大ざっぱにまとめます。例えば「科学者が決めてよいですか?」とフレーズを引っ張っていますが「何%なら『科学的』ですか?」ということは決まっていません。ロシアンルーレットが1%だったらどうか。やる人はいないでしょう。先ほどお話ししたように、例えば試験があるなどというときに解熱剤を飲んではダメですか?これは科学的根拠に基づけばダメですと言う人も多分いないでしょう。今日は法律家の方もたくさんいらっしゃっていると思いますが、民事事件と刑事事件では、判決に必要な証明度というのは大きく異なります。ではこれは非科学的なのでしょうか。これも多分議論の必要はないかと思います。

Now, I will briefly summarize what I have just told you. I’ve raised here the question “May scientists make decisions for others?” But there is no definition as to what level of probability (%) would be deemed as being “scientific.” What if the risk for being shot was reduced to less than 1% in Russian Roulette? I still don’t think anyone want to try it. Let’s get back to the other example I was talking about. When someone has to take an important exam, I don’t think anyone would say “you shouldn’t take antipyretics because it’s wrong based on scientific evidence.” I think we have many legal experts here with us today. I understand the level of proof required to reach judicial decision is very different between civil and criminal cases. Well, is that unscientific? I suppose we don’t need to discuss this question either.

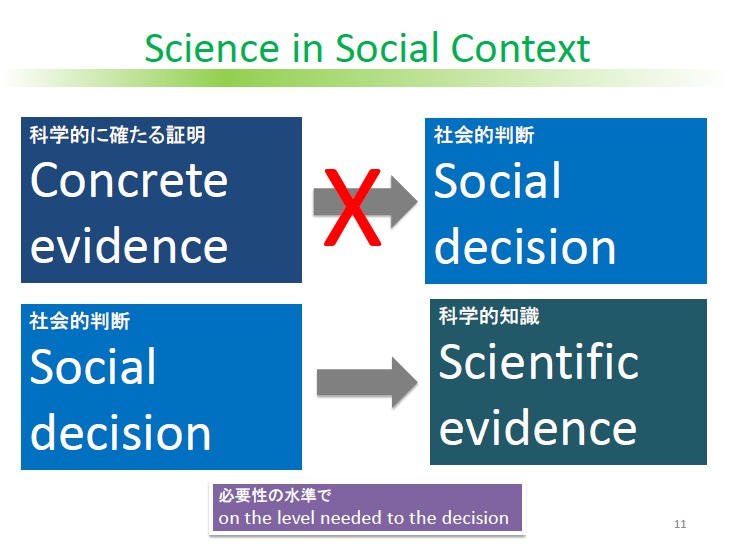

♦11

つまり社会的な判断というのは、科学的に確たる証明があってなされるものでは、必ずしもないということです。そしてむしろ、社会的判断に必要なレベルで科学的知識を使う、もちろん科学的知識を最大限に使うということは望ましいしそうあるべきだと思いますが、ではどこで科学的知識をもとに判断するかというのは、科学で決まるものではありません。このことを確認した上で法廷の話に入りたいと思います。

What I wanted to say is that social decisions are not always made based on clear and definite scientific evidence. Rather, scientific knowledge is utilized to a level necessary in social decision making. Needless to say, it is desirable to make the most of scientific knowledge, but it is not a task of science to determine the timing when a decision has to be made based on scientific evidences. I wanted to make this point clear before talking about the things going on in court.

♦12

今日は法廷を舞台に今お示ししたような問題を考えていきます。法廷は科学的知識を社会的判断に生かすもっとも典型的な場所の一つです。そこで実際に法廷でどういうことが起こっているのかを、実例を挙げながら考えてみたいと思います。

Today, I will take some examples from court cases to think over issues I have just mentioned. The court is a typical place where scientific knowledge is utilized in social decision making. So here, I would like to show some examples of what is actually going on a court.

♦13

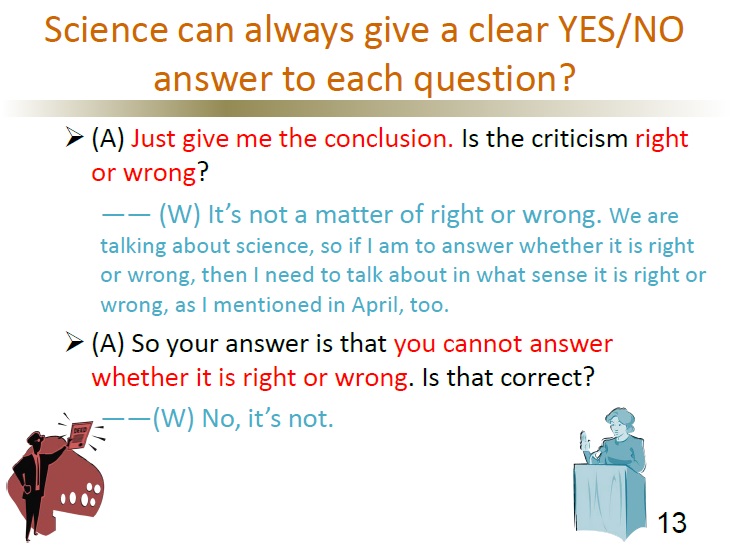

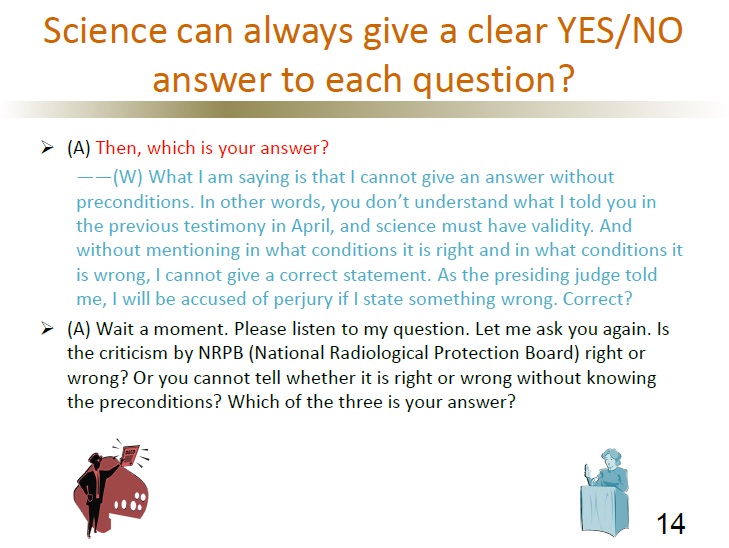

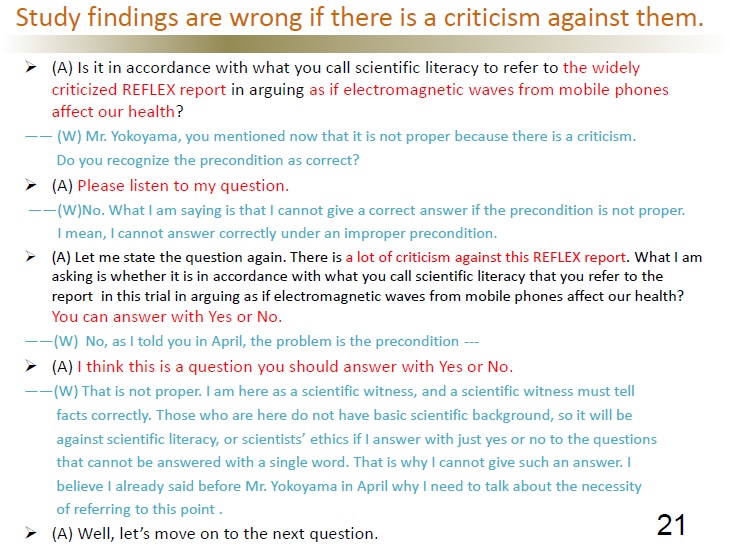

これはある日の法廷で、実際に行われたことです。弁護士の人が、科学者証人という人に、質問をしています。「結論だけ答えてください。その批判は正しいですか、正しくないのですか」。「いや、正しい、正しくないというか、まあそういう正しい、正しくないでは答えられない」というふうに、証人が答えます。そうすると弁護士の方はこう言います。「正しいか正しくないかを答えられないというお答えでよろしいのですか」。「いや、違います」と言うと、「ではどちらですか」ということで、とにかく正しい、正しくない、YesかNoかということで質問を繰り返す、そういう光景が実際に起こっています。これは日本の法廷ですけれども、今日来ていただいているオーストラリア、マクレラン判事が裁判官をなされているオーストラリアでも、コンカレントエヴィデンスという新しい方式が始まる前は、同様の光景が繰り返されていました。

今日は時間の関係でこれをすべて読み上げることはいたしませんが、この尋問の全記録を展示コーナーに置いておりますので、興味のある方は全文すべて読むことができますので、お手にとってご覧いただければと思います。

This is a conversation that actually took place in court one day. The attorney questions a scientific expert witness, “Just give me the conclusion. Is the criticism right or wrong?”

“Well, it’s not a matter of right or wrong . . . I can’t just plainly answer if it is right or wrong” replies the witness. Then the attorney says “So your answer is that you cannot answer whether it is right or wrong.

Is that correct?” “No, it’s not.” The attorney asks again “Which is it then?” . . . and it goes on like that repeating the question whether it is right or wrong, and demanding an answer of either “Yes” or “No.”

This is something you actually encounter in court. This example was taken from a Japanese court, but similar scenes were often seen in Australia’s court, too, where Justice McClellan serves,

until the new system of concurrent evidence was introduced.

Today I don’t have enough time to read out the entire record of this hearing of the expert witness, but there is a copy in the exhibition corner, so please take a look through it if you are interested.

♦15

この証人尋問はいつなされたかというと、これは平成20年ですから4年前ですか、4月14日午後1時30分からなされました。ここに見えるでしょうか、これは私の名前でして、私が証人尋問として呼ばれたときの尋問の光景です。

This hearing took place in 2008, so that’s 4 years ago. It started from 1:30 p.m. on April 14. You see this name here? It’s my name on the writ of summons. This conversation was what I experienced when I was summoned as an expert witness.

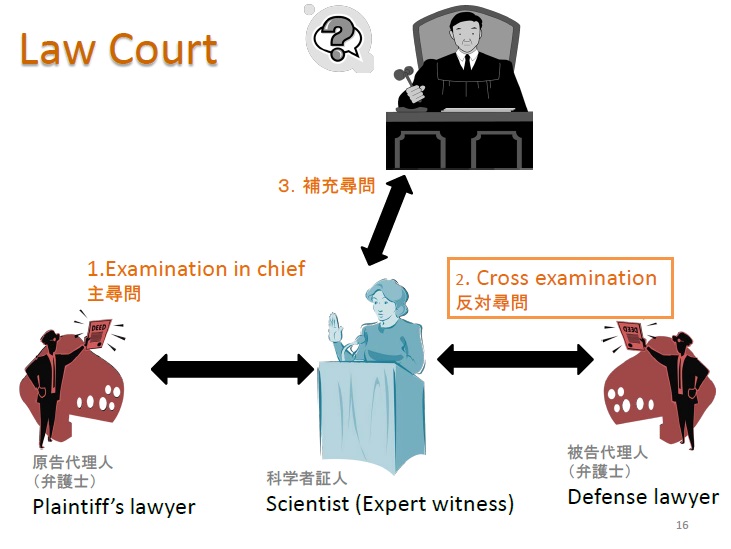

♦16

今の尋問はどういうものかといいますと、この方が裁判官ですね。原告代理人の弁護士がいて、被告代理人の弁護士がいます。科学者尋問というのは、まず最初に原告代理人から科学者に対してなされる、これを主尋問といいます。その次に被告代理人から科学者証人に対して尋問がなされます。これを反対尋問、Cross Examinationと呼びます。先ほど示した光景は反対尋問、Cross Examinationでの光景です。つまり原告側が証人申請した証人に対して、被告側の弁護士が反対尋問を行って、科学者証人をやっつけようとしているという光景です。

Let me explain what a hearing in court is like. You see, this person is the judge. The plaintiff’s lawyer sits here, and the defense lawyer, here. A hearing of a scientific expert witness starts by questions from the plaintiff’s lawyer. This is called an examination in chief. Next, the defense lawyer asks questions to the expert witness. This is called a cross examination. The conversation I presented earlier was part of the cross examination. To put it plain, it was a scene in which the defense lawyer was trying to tear down the expert witness called to the stand to testify on behalf of the plaintiff.

♦17

反対尋問に関する本、いわゆる法学の本をひもとくと、このようなことが書いてあります。反対尋問というのは、最も確実な真実の吟味法であると書いてあります。これはその反対尋問を含めた、弁護士が法廷でどのような尋問をすべきかが書いてある、大変有名な本です。

When we refer to a law book about cross examinations, you find explanations like this. “Cross examinations are the most reliable of means for examining the truth.” This is a very famous book instructing lawyers how to ask questions in court, including questions to be asked in cross examination.

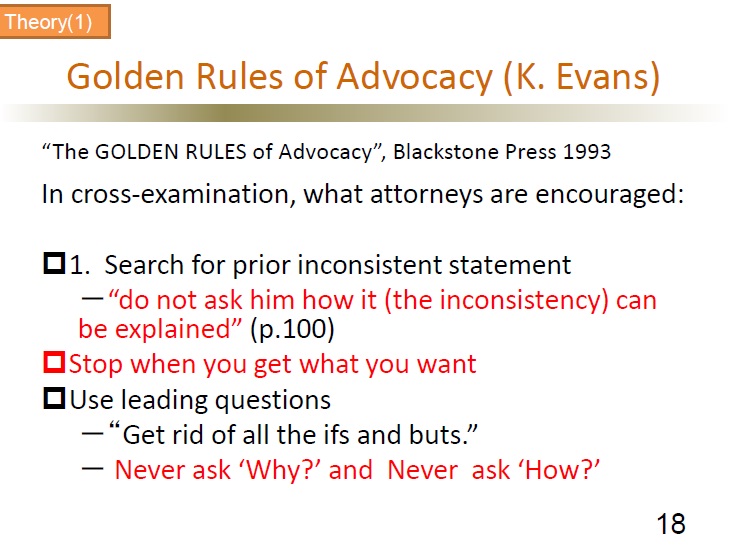

♦18

The Golden Rules of Advocacyと書いていますが、これはイギリスの弁護士が法廷弁護士をやっているキース・エヴァンスという方が書いた本で、日本語にも翻訳されています。日本でこの本に書かれているやり方の尋問は、非常に日常的に行われております。実際どのような内容かを、この本のエッセンスをちょっと見てみましょう。

それから外国人参加者の方は、これは日本語だけで書いているので、お配りしてある紙の資料のページ2をご覧いただければ、スライドの英語版バージョンがあるので、そちらを実際見ていただければよいかと思います。

そのゴールデンルールでは、このようなことが書いてあります。

「誘導尋問を用いよ」、つまりYes、Noで答えさせるということです。「もしも」「けれども」などは全部除いて、「なぜ(why)」「どのように(how)」というのは決して尋ねてはいけないということです。つまり証人に説明させてはいけないということです。それと同時に、証人というのは代理人の質問、代理人というのは弁護士ですけれども、その質問にしか答えることができないという制度になっています。

“The Golden Rules of Advocacy” was written by Keith Evans, a trial attorney practicing in England. It’s been translated into Japanese. The methods introduced in this book are very common practice in Japanese courts, too. Here I will show you a few excerpts to give you an idea of the essence of the book. For those of you from abroad, this is written only in Japanese, so please refer to page 2 of the material that you have at hand. It shows an English version of the slide.

Well, the “Golden Rules” says things like these.

“Use leading questions.” In other words, this means to make the witness answer by either “Yes” or “No.” The book instructs attorneys to get rid of all the “ifs” and “buts” and never ask “Why” or “How.” What this is trying to say is don’t let the witness explain for himself. The court system forbids the witness to say anything other than answers to questions made by the attorneys. The witness is not allowed to talk for him or herself.

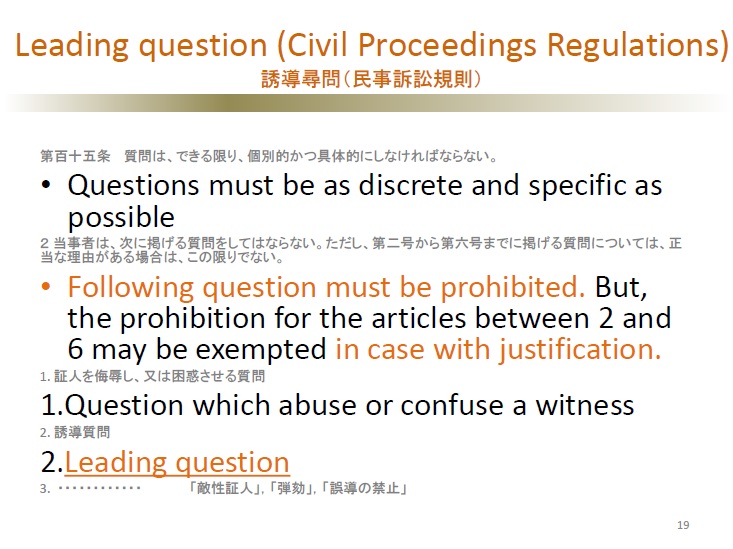

♦19

ここで、ある程度法律に詳しい方は、このような疑問を持つかもしれません。それは誘導尋問は禁止されているのではないかという質問です。確かにこれは民事訴訟規則というもので裁判所が決めているものだと思いますが、その中では、誘導尋問というのは、基本的に禁止されています。禁止されていますが、実際には例外的に認められる、つまり正当な理由がある場合にはこの限りではないと書いてあり、正当な理由があるのでやっていい、つまり反対尋問というのはやっつける場面だからやっていいというような解釈が普通です。実際に毎日のように行われています。

私はこの尋問に出るときに、東北大学の授業を2回ほど、学生を置き去りにして、大分まで行って、先ほどのような誘導尋問を受けるということになっているわけです。

Hearing this, those of you who are sort of familiar with law may think that leading questions are supposed to be prohibited. Yes, that’s right. The Civil Proceedings Regulations, which I think the Supreme Court created, prohibit leading questions as a basic rule. They are basically prohibited, but actually, there are exceptions to this rule. It’s written here “. . . however, these shall not apply when there are justifiable grounds.” So, if one thinks that there is a justifiable reason, he or she can ask leading questions. And because cross examinations are considered as a legitimate opportunity for knocking down the opponent’s claims, it is normally accepted to use leading questions as ammunition. As a matter of fact, leading questions are everyday practice in court.

I had to abandon my students for two classes to go all the way down to Oita and testify, to be asked leading questions like I showed earlier.

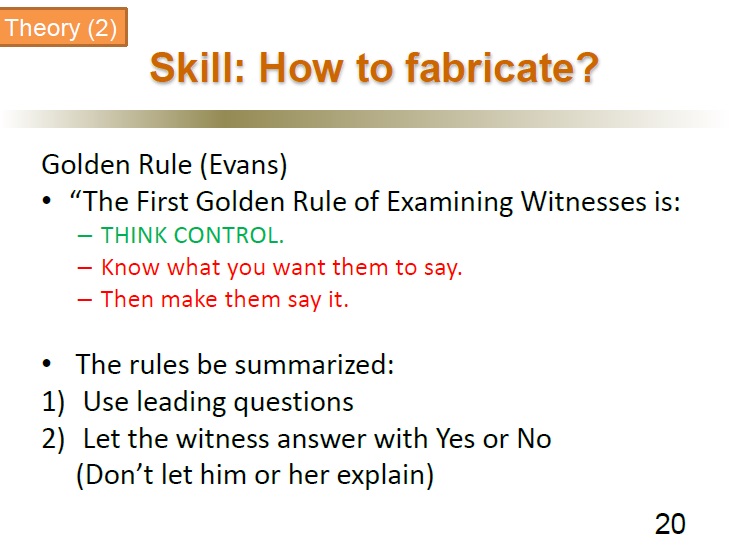

♦20

もう一度先ほどの、弁護のゴールデンルールに戻ると、そこでは彼らに何を言ってほしいかを知り、それから彼らにそれを言わせよというふうに書いてあります。つまり誘導によって望みどおりの結果を得ましょうと。それが弁護士の使命なのであるということが、書いてあります。これが誘導尋問を行う目的です。

Going back to those “Golden Rules” for attorneys, it says on this book that “you have to know what you want them (i.e. the witness) to say, and make them say it.” The book encourages attorneys to use leading questions for getting the desired results, because that’s the attorney’s mission. That’s the purpose of using leading questions.

♦21

もう一度ここで法廷の様子を見てみましょう。例えばこのような、これは先ほどの尋問の続きですが、「これだけ多くの批判がなされている報告を持ち出して、健康に影響があるかのような議論をすることは、それはいいのですか」と言ってきます。それに対して批判のない科学研究というのはないので、そのように答えると、「いや、質問を聞いてくださいね」というふうに、もう一度尋ねられます。それで「いや、それはちょっと何かおかしいのですが」というふうに言うと、また弁護士の方が「たくさんの批判がされている、そういう研究を持ち出して、健康に影響があるかのような議論をするということは、これはおかしくないですか」と言ってきます。またここで言うのです。「YesかNoで結構ですから、答えてください」。ここで「いやそれはちょっとおかしい」ともう一度言うと、「いや、もう一度、はいかいいえで答える質問だと思うんですが」ということを繰り返します。もちろん科学的にはYes、Noで答えられないことだらけなのですが、こういうことになります。なぜかというと、これは誘導尋問をやっているからです。誘導尋問でYesかNoで答えさせるというのがセオリーになっているからです。

3.11以降も明らかになったように、世の中には科学技術に伴う不確実性の大きな問題というのがたくさんあります。この不確実性が大きな問題を扱うと、非常にこれは不毛な議論になってしまうということを、これからまたお話しいたします。

Now, let’s go back to how the cross examination went in court. Following the questions and answers I showed earlier, the attorney asked “You have referred to a widely criticized report in arguing as if electromagnetic waves from mobile phones affect our health. Is that truly based on what you call scientific literacy?” So I answered that no scientific research is free from criticism. Then he says, “No, no. Please listen to my question” and asks the same question. So I tell him again that I can’t agree with the precondition for the question. Then the attorney asks again “There is a lot of criticism against the report you referred to. Is it really reasonable to refer to such a report in arguing as if electromagnetic waves from mobile phones affect our health?” and adds “Please answer. Just answering with either yes or no is enough.” I tried to point out again that what he was saying was not making sense to me, but he cuts in repeating that “this is a question you should answer with yes or no.” Needless to say the question contained many aspects which you cannot scientifically answer with yes or no. But the examination ends up in an argument like this. This is because the attorney is intentionally asking leading questions. It’s a standard methodology to force the witness to answer with yes or no using leading question.

As it has been revealed through the events following the 3.11 earthquake, there are a lot of problems involving a lot of uncertainties pertaining to science and technology. When we deal with these problems with a lot of uncertainties, it tends to end up in pointless controversy. I’m going to explain about that later.

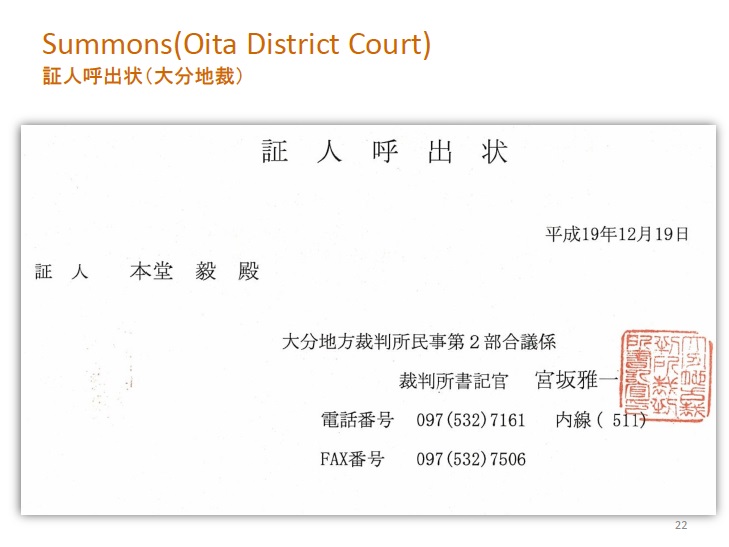

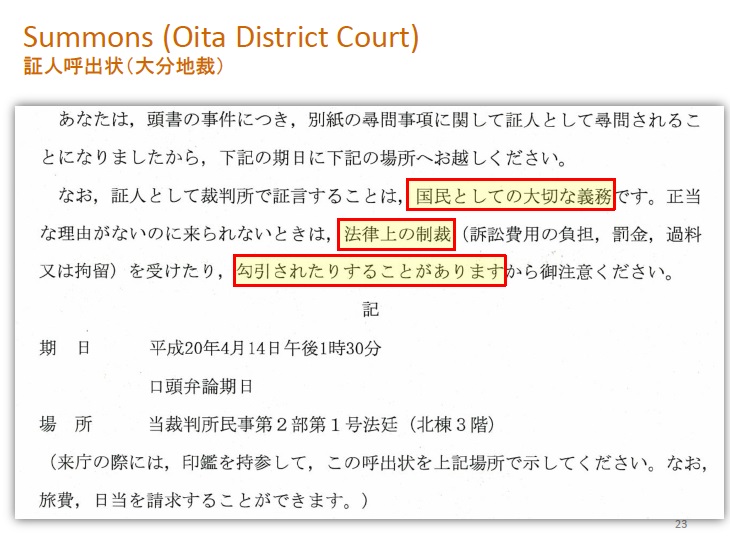

♦22-23

これが先ほどの証人の呼び出し状です。証人尋問というのは、弁護士に呼ばれるのではなく、裁判所に呼ばれます。裁判所から来てくださいということで、「証人として裁判所で証言することは、国民としての大切な義務です。正当な理由がないのに来られないときには、法律上の制裁(訴訟費用の負担、罰金、過料あたは拘留)」、すごいですね、「を受けたり、勾引されたりすることがあります」。つまりそこに行かないともう大変なことになってしまうという、非常に怖いものが、これは私の自宅に送られてきたわけです。行かないわけにはいかないわけです。つまり承認というのは裁判所の依頼で公的な役割として出廷するということです。

Please take a look, this is the writ of summons I received. Expert witnesses are summoned by the court, not the attorneys. It says here “It is an important part of your obligations as a citizen to testify in court as a witness. If you do not turn up in court without a justifiable reason, you may face sanctions including bearing of court costs, penalty, non-penal fine or detention or be subpoenaed.” Oh my . . .so if I don’t show up in court something really bad may happen. I can say something very scary was sent to my home. I had no choice, because testifying as a witness is a public obligation imposed by the court.

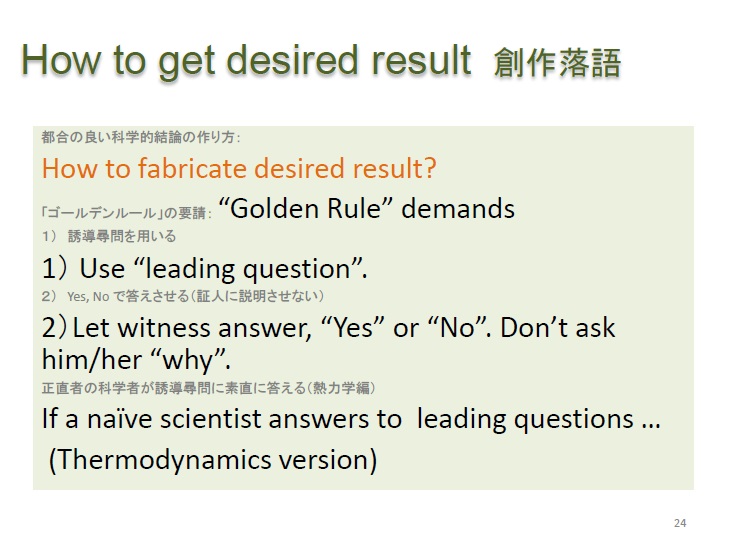

♦24

その承認尋問と誘導尋問というものの本質をちょっと分かりやすく見るために、一つ創作落語を作ってみました。それでこの辺りはマクレラン判事がとても、マクレラン判事は裁判官になる前に法廷弁護士で、特に反対尋問が得意であった。だから本当はマクレラン判事にこの辺りの話は説明してもらった方がよいぐらいなのですが、ちょっと私が説明いたします。

先ほどの話を繰り返しますが、誘導尋問を使って、Yes、Noで答えさせるということをやって、それで科学的な知見をいじるというか取り扱うとどうなるかということを見てみましょう。

先ほどの尋問の場合は、私はちょっとひねくれていて、尋問に行く前に民事訴訟規則であるとか民事訴訟法であるとか弁護のゴールデンルールなどをすべて読んでいました。なぜならば自分が話していないことが自分が話したように作られてしまうということは、私の行動規範、つまり科学者として、それは私のルールというか、規範、誠実性、科学者としての私が考える誠実性に反する、正しいことを正しく伝えるのが科学者としての義務であると思っていましたので、ねじまげられないように私は頑張ったのですが、ここでは非常に正直な科学者が、誘導尋問に素直に答えるという状況で、何が起こるかというのを見てみましょう。

I made up a fable, a comic story to illustrate the essence of cross examination and leading questions. Perhaps Justice McClellan could explain this better than me. He used to be a trial attorney before he became a judge and I heard he used to be really good at cross examination. But anyway, since I made this story I’ll tell it.

This little story was invented to show what happens when the attorney tries to play with scientific knowledge by making the expert witness answer with only yes and no.

In my case, I am not a kind of obedient, so I had already read the Civil Proceedings Regulations and the Code of Civil Procedures as well as “The Golden Rules of Advocacy” prior to attending court, because I didn’t want anyone to twist around what I said as if I said something I really didn’t. That would be against my “golden rule” or my norm or integrity as a scientist. I believe it is the responsibility of a scientist to maintain scientific integrity, and to convey correct knowledge as correctly as possible. But here in this fable, a very docile scientist answers leading questions, and see what happens.

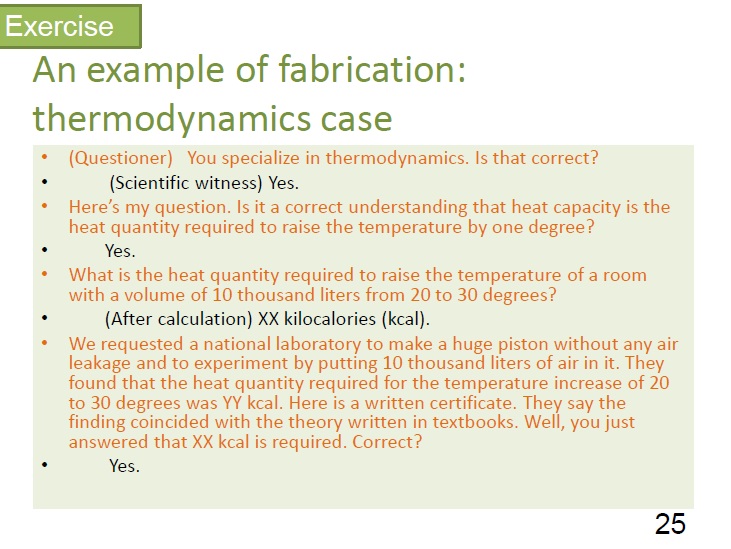

♦25

今からお話しするものは、熱力学という、大学1年生ぐらいの物理の話です。私は物理学者ですので、実際に熱力学を大学で教えています。その論文も書いています。それを例にとってちょっと見てみましょう。

弁護士が科学者に尋問しています。

(A)「証人は、熱力学をご専門にされていますね」

(S)「はい」

(A)「そこでお尋ねします。『比熱』とは、温度を1度上昇させるのに必要な熱量という理解でよろしいですか」

(S)「はい」

(A)「1万リットルの容積を持つ部屋を、20度から30度に暖めるのに必要な熱量はいくらですか」

(S)「××キロカロリーです」

(A)「一応私たちのところで別の専門家に委託して、空気が漏れないように巨大なピストンを作って1万リットルの空気を入れて、実験をしてもらったのです。すると、20度から30度にあたためるのに必要な熱量は、△△キロカロリーになったそうです。ここに鑑定書もあります。これは、理論的な計算とも一致しているそうです。さて、先ほど、証人が、××キロカロリーとおっしゃいましたね」

(S)「はい」

(A)「尋問を終わります」

終わりです。笑っている方は分かっているわけですが。

This story has to do with thermodynamics, requiring knowledge level of perhaps a freshman student in physics. I’m a physicist and I teach thermodynamics. I’ve written some articles in the area, too. So let’s take this area of science for example.

The attorney questions the scientist.

(A) “You specialize in thermodynamics, is that right?”…

(S) “Yes”

(A) “Here’s my question. ‘Heat capacity’ is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature by one degree Celsius. Is my understanding correct?”

(S) “Yes”

(A) “What is the heat quantity required to raise the temperature of a room with a volume of 10 thousand liters from 20 to 30 degrees?”

(S) (After calculation) “×× kilo calories”

(A) “We requested a laboratory to make a huge piston without any air leakage and to experiment by putting 10 thousand liters of air in it. They found that the heat quantity required to raise the temperature from 20 to 30 degrees was YY kcal. Here is a written certificate. They say the experiment result perfectly conforms to theoretical calculations. But you just answered that XX kcal is required, didn’t you?”

(S) “Yes”

(A) “I’m through with my questions.”

How was that?

. . . Those who are laughing must have already got the trick.

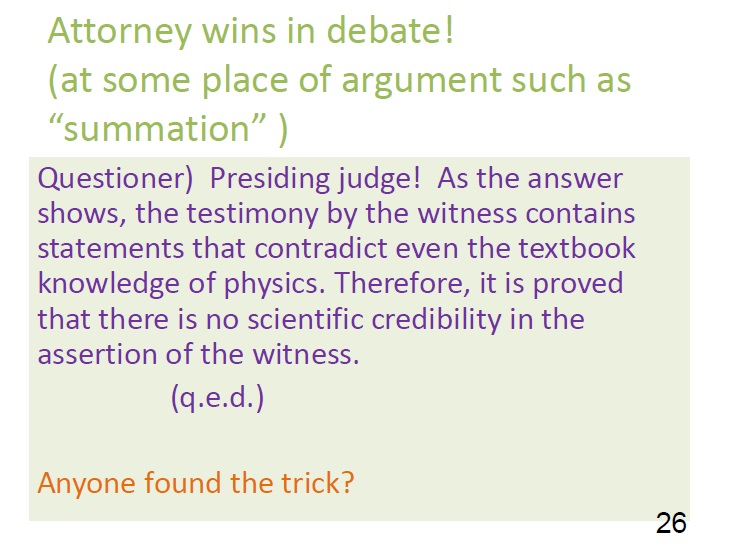

♦26

その後、後日、「裁判長、このように、証人の証言には、物理学の基礎にさえ矛盾する内容が含まれており、証言には、なんら科学的信憑性がないことが証明されました」という、実際このようなことが繰り返されています。ちょっと伺いたいのですが、今のトリックが分かった方は手を挙げていただけますか。ありがとうございます。何人かの方は分かりました。多分分かった方は物理学や化学の素養のある方だと思います。ただ分からない方もかなりいますよね。おそらく法廷では、分からない方も結構いるはずなのです。これが通ってしまう可能性があります。実際にこういうことが法廷で通っています。そういう尋問調書は、どうぞ調べてみてください、たくさんあります。これが今の日本の法廷での科学の現実なのです。

Later, on another day, the attorney says to the judge “Your honor, the testimony of the witness contains statements that contradict with even the very basics of physics and is proven to lack scientific credibility.” These kinds of things actually go on in court. May I ask how many of you got the trick? Could you please raise your hand if you found the trick? Thank you. Some of you got it. I think those are people familiar with physics or chemistry. However there are also many who didn’t. I suppose many people in court wouldn’t recognize the trick. Then this kind of trick could be overlooked in court. In fact, they are being overlooked. I’m sure you will find many examples like this in witness examination records. This is the reality of how science is treated in court in Japan today.

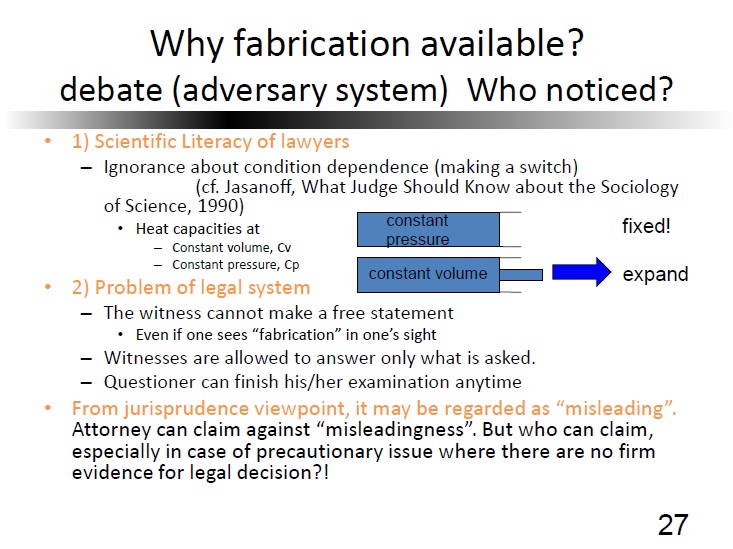

♦27

これは事実でないことを事実のようにこしらえていることです。これは、英語で敢えて書きましたが、広辞苑の、ねつ造の定義です。

つまり、真実解明の場、つまり法廷で、ねつ造合戦が日々行われているというのが、偽らざる事実です。良い悪いは別にして、事実です。今のは、ここはちょっと細かい話ですが、科学というのは、さまざまな条件によります。例えば今の場合は、体積を一定であたためるか、あるいはピストンのように圧力を一定であたためるかによって、条件が違うわけです。その二つの条件を切り替えてしまった、すり替えてしまったということで起こったねつ造なのです。これは証人尋問の尋問制度の問題と非常にかかわるわけです。つまり証人には自由に発言する権利はありません。目の前でねつ造が行われても、言えません。「ストップ、終わりです」と言われたら、何も言えないのです。尋問者の発問に答えるのみです。尋問者が自由に質問を打ち切れるということです。これが今の法廷のシステム、制度です。

This means that something that is not actually true is being manipulated into looking like facts. “To fake something that is not true as if it is true,” this is the meaning of “fabrication” as found in Kojien (an authoritative Japanese dictionary).

I must say that fabrication of facts is a daily practice in court, which is supposed to be a place for finding the truth. Regardless of whether it’s good or bad, that is the plain truth. Let me explain the trick of the fable. I must go into the details here. Science depends on various conditions. For example, as in the story above, heating a substance under a given volume (as in the case of a room) and under a given pressure (as in the case of a piston) are two different conditions, and accordingly have different results. In the story I told you, these two conditions were switched. And that’s how the facts have been manipulated. This manipulation is strongly associated with the system of witness examination. The witness does not have a right to freely talk or explain. The witness cannot point it out loud even if he or she sees the facts are being manipulated or fabricated right in front of them. If the attorney says “That’s it, stop,” then the witness must shut his/her mouth. You can only answer the questions asked, and the attorney can make you shut up anytime he/she wants. This is how the current system works.

♦28

一方で科学者、私たちに対しては、さまざまな行動規範なりルールというか倫理が課されています。ここに書いてあることは、結果を勝手につくりあげる行為(ねつ造)はやってはいけません、科学者としての生命が危ぶまれて、最後には厳しい罪が下されるのだと書いています。これは非常に有名な、アメリカ科学アカデミーから出されている、出版されている本で、多くの学生たちに、日米どちらでも、読まれています。日本語にも翻訳されています。池内さんが訳しています。

In contrast, we scientists are bound by various norms, rules and ethics. We are not allowed to fabricate scientific facts. It’s written in this book that if we do (fabricate scientific facts), we will risk our career as a scientist, and ultimately be severely punished. This is a very famous book published by the U.S. National Academy of Science. It is read by many students both in the US and Japan. It’s been translated into Japanese by Mr. Satoru Ikeuchi.

♦29

その本をもう少し見ると、不正行為を犯した場合どうなるかと書いてあるのですが、裁判所なども巻き込む容易ならざる事態になるかもしれないと書いてあるのです。巻き込むと書いてあるのですが、これ裁判所でやっているのです。だから裁判所にいって大変なことになりますよとやっている裁判所でそういうことがなされているのが現実です。

今お話ししたことは、始めて聞いた方はびっくりされるかもしれませんが、これはよく知られている話なのです。私の個人的な意見では決してありません。

マクレラン判事がコンカレントエヴィデンスを始めた理由も、今までの対審行動といいますが、こういうYes、Noで答えさせて、科学者をある意味、科学的事実をグジャグジャにしてしまうというような、そういう尋問が不毛だということで、コンカレントエヴィデンスを始めたわけです。これはマクレラン判事も登場しますが、ニューヨークタイムズのAmerican Exceptionというものの中でも、実はアメリカでも同じ状況がうまれていて、問題になっているということが、よく書かれています。これはウェブページで日本でも読めますので、興味のある方はご覧ください。

それから今年の7月にフランスの法学者、Munagorriさんというナント大学の方で、この人はフランスの科学と法の研究ネットワークの代表をしている方で、数百人の法学者が参加している組織の代表なのですが、この人も、「はいはい、あれね、もちろん知っています」。もちろんアメリカの法学者、エキスパートエヴィデンスという分野があるのですが、その法学者もよく、科学と法について考えている人なら皆さんよくご存じの、非常にスタンダードなことです。

In this book, it also says on this book that misconducts could lead to serious trouble including being accused in court. But in that court itself, facts are being manipulated and fabricated. The court which is supposed to administer justice allows facts to be fabricated right within it.

Some of you may be surprised to hear this, but it’s really nothing new. It is a well known fact and never my personal view.

After all, this is the reason why Justice McClellan established the system of Concurrent Evidence, in recognition of how scientific facts are being manipulated and rendered useless in conventional court procedures by making scientists answer by either yes or no. This is an article from “American Exception,” a series of articles in New York Times examining various aspects of the U.S. justice system. It describes how similar problems are causing concern in the US, too. The article also mentions Justice McClellan, so please take a look if you are interested. It can be accessed on the Internet. Japanese version is also available.

Professor Munagorri, a French legal scholar from the University of Nantes, who is also president of a French research network on science and law with several hundreds of jurist members. He also said “Ah yes, that, of course I know.” Another legal scholar from U.S., a specialist in expert evidence told me he was also very well aware of this problem. So I think it can be said that it is a commonly recognized problem among those who are studying about science and law.

♦30

先ほどお話ししたように、先ほどの熱力学というのは、いわゆる正解がある世界ですが、現実にはさまざまな不確実性を帯びた現象が法廷で扱われるわけです。つまり未来予測などが扱われるわけです。そうするとこの問題は非常により深刻な問題を招いてしまいます。なぜならば、未来を扱う、不確実性が高い問題というのは、ほとんどが推測です。絶対こうなるなどという知見はありません。先ほどの地球温暖化もそうですが、絶対こうなるという知見がないときには、さらにグジャグジャというか不毛な議論になってしまいます。なぜなら確たる証拠がないからです。

さらに先ほどの熱力学であれば正解があるからまだいいのですが、不確実性が高い問題の場合には誤導、これは法律用語ですが、ミスリーディングですね、誤った結論を強引に導いているのだということを弁護士が相手の弁護士に指摘してやめさせるということは、できるのですが、弁護士の人はそれは分かりません。分かるのはおそらく証人だけです。という問題がまずあります。

それともう一つ、先ほどの「ただちには影響はない」にも関係するのですが、何を知りたいか、何を議論すべきかに関する多義性、Ambiguityですが、に関する問題が出てきます。それをもう一つ、創作落語をお見せしながらご説明します。

As I already mentioned, in thermal dynamics a “correct” answer can be determined through theoretical calculations. However, there are many phenomena being dealt with in court that are associated with various uncertainties. In other words, issues such as prediction of the future are being examined in court. In such cases, the problem becomes much more serious. Problems relating to future and bearing uncertainties and rely mostly on predictions. No one can tell exactly what will happen in the future. Like with the issue of global warming we saw earlier, the argument can become even more meaningless when there is no definite knowledge or evidence as to what will happen in the future.

The situation is much easier in such cases as my fable of thermo dynamics, because there is a correct answer. In cases that are highly uncertain the opposing attorney has a right to point out that the other attorney is “misleading” the witness and make him stop doing that. But the problem is that the opposing attorney wouldn’t be able to tell whether the other attorney is attempting to mislead the witness unless he has sufficient scientific knowledge. The witness is probably the only person who can notice the intentions of misleading. This is one problem.

Another problem (and this is related to the phrase “no immediate effect”) is the ambiguity regarding what we need to know and what should be discussed. I’ll explain this problem using another story I made.

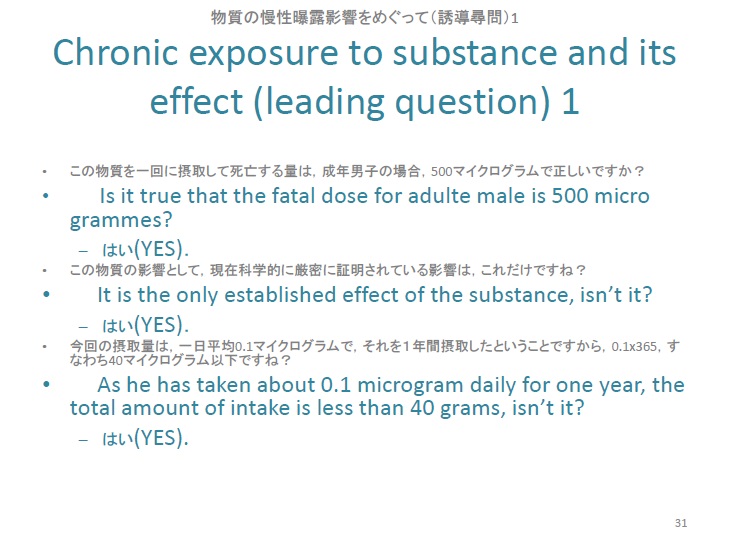

♦31-32

これはある物質、何か架空の物質の慢性曝露影響をめぐって誘導尋問をやったらどうなるかということで、例を作ってみました。ちょっと読んでみましょう。慢性影響というのは、例えば10年、20年後にどういう影響が出てくるか、そういう物質を、微量であってもずっと受け続けた場合にどういう影響が出てくるかということです。

弁護士(A)が「この物質を一回に摂取して死亡する量は、成年男子の場合、500マイクログラムで正しいですか」

素直な科学者(S)が「はい」

(A)「この物質の影響として、現在科学的に厳密に証明されている影響は、これだけですね」

(S)「はい」

(A)「今回の摂取量は、1日平均0.1マイクログラムで、それを1年間摂取したということですから、0.1に365をかけて、40マイクログラム以下ですね」

(S)「はい」

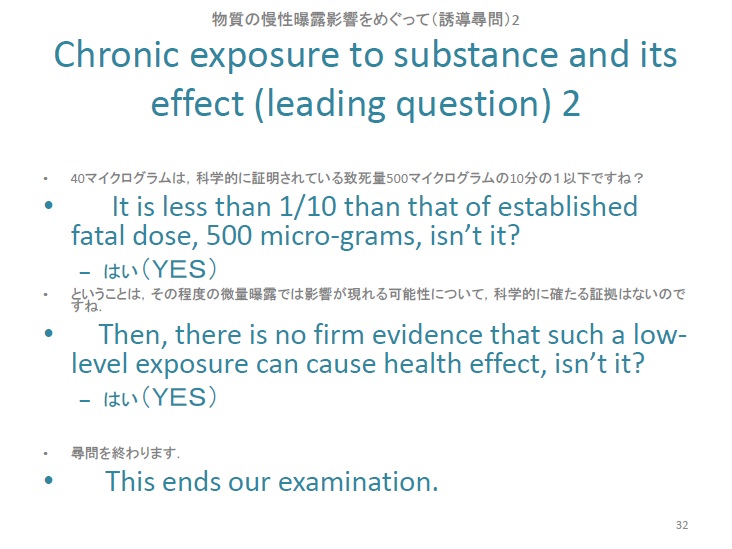

(A)「40マイクログラムは、科学的に証明されている致死量500マイクログラムの10分の1以下ですね」

(S)「はい」

(A)「ということは、その程度の微量曝露では影響が現れる可能性について、科学的に確たる証明はないのですね」

(S)「はい」

(A)「尋問を終わります」。

I made this story as an example of what would happen if an attorney tries to ask leading questions on the effects of chronic exposure to a substance. I have no particular substance in mind, it’s an imaginary one. The term “chronic effect” refers to the effects that will appear after continuous exposure to even a trace amount of that substance through a time span of 10 or 20 years.

If the attorney asks “Is it true that the fatal dose for adult male is 500 micro grams?” a docile scientist would answer “Yes.”

(A) “It is the only scientifically proved effect of the substance, isn’t it?”

(S) “Yes, it is.”

(A) “As he has taken about 0.1 microgram daily for one year, the total amount of intake is less than 40 grams, isn’t it?”

(S) “Yes.”

(A) “It is less than one tenth of established fatal dose, 500 micro-grams, isn’t it?”

(S) “Yes.”

(A) “Then, there is no firm evidence that such a low-level exposure can cause health effect, isn’t it?”

(S) “Yes”

(A) “This ends our examination.”

♦33

多分こういう光景を見せられた多くの人は、非常にストレスを持つと思うのです。なぜストレスを持つのでしょう。何かおかしいわけです。でも一見科学的には厳密ですね。科学的に間違ったことはやっていないように見えますよね。ある意味科学的に正しいのです。でも何か違和感があります。それは先ほどの「ただちに影響はない」と同じような違和感だと思います。

If people saw a scene like this, I’m sure most of them would feel very frustrated. That’s because something’s wrong. Seemingly, there’s nothing wrong scientifically in the context. It seems scientifically rigorous and it is correct in a sense. But we feel something is wrong. I think this is the same kind of unconvincing feeling we get when we hear the words “No immediate effect.”

♦34

これはどういう問題かというと、科学というのは何か一つの対象を選ばないと、厳密な議論ができないわけです。例えば急性影響と慢性影響という二つの側面があって、急性影響だけが科学的にはっきり分かっているというようなことは、たくさんあります。これはもういろいろな分野でたくさんあります。大体研究というのは急性影響の方から進んでいきます。分かりやすいですから。それで今は致死量についての尋問があったわけですが、先ほど慢性影響を議論する場として、何か例えば裁判が起こったとします。その慢性影響を知りたいのに、なぜか急性影響だけの議論で、科学的に確立されていることはこれだけですね、で議論が終わってしまったということです。

実際には何か物質を、病的な原因になる物質を得たときに何が起こるかというのは、死だけではありません。例えばずっと頭痛が続くとか体が痛いとか、さまざまなQOL、生活の質に関係するような慢性影響というのは当然あるわけです。例えば非常に典型的な例として、私も学会に所属しているシックハウス、私も医学会にも入っていますが、そのシックハウス症候群というのは、急性影響での致死量に比べるとものすごく、何万分の1や何十万分の1などという微量を少しずつ浴びていることによって起こったりします。このシックハウス症候群があるということは皆さんよくご存じだと思いますが、例えばそのようなことを気にしているのに、なぜかこちらの方だけ議論が行われてしまう、そしてこちらは切り捨てられてしまうということがよく起こります。これは裁判官にとっても非常に不幸でしょう。つまり裁判官が知りたいことが全然議論されずに尋問が終わってしまうということです。裁判以外でも、やはり市民が知りたいことがなぜかはぐらかされて、一見科学的には厳密なのだけれどずれた議論が行われてしまうということが、少なからず起こります。

Science requires us to choose one single object, in order to build a scientifically rigorous discussion. For example, the overall effect of exposure to a substance consists of two different aspects, acute and chronic. Very often, only the acute aspects have been scientifically confirmed. This kind of situation is seen in the various fields. In general, acute effects are studied first, because they are more apparent. The attorney asked about the fatal dose which is an acute effect. But as I said before, the purpose of this trial was to discuss the chronic effects of exposure to the substance in question. We want to know about the chronic effects but the attorney is only asking about the acute effects and ends the discussion after confirming that acute effects are the only effects that have been scientifically proved so far.

In fact fatality is not the only unwanted effects of a substance. It could cause a chronic headache or other kinds of pain, and various chronic effects that would impact quality of life. A typical example is the sick building syndrome. I’m a member of a researcher society on the sick building syndrome. It has been found that sick building syndromes can be triggered by exposure to extremely small amounts of certain substances, parts per thousands or millions of the fatal dose of that substance. I’m sure you all know about this sick building syndrome. It’s a famous problem, but still, the chronic effects caused by trace amounts of substances are not discussed in court, they’re being ignored. This is a tragedy for the judges. Because what the judges want to know most is not being discussed in the expert witness examination. The same things often happen outside the court, too. What the citizens want to know is somehow quibbled and the seemingly scientific discussion keeps going off the point.

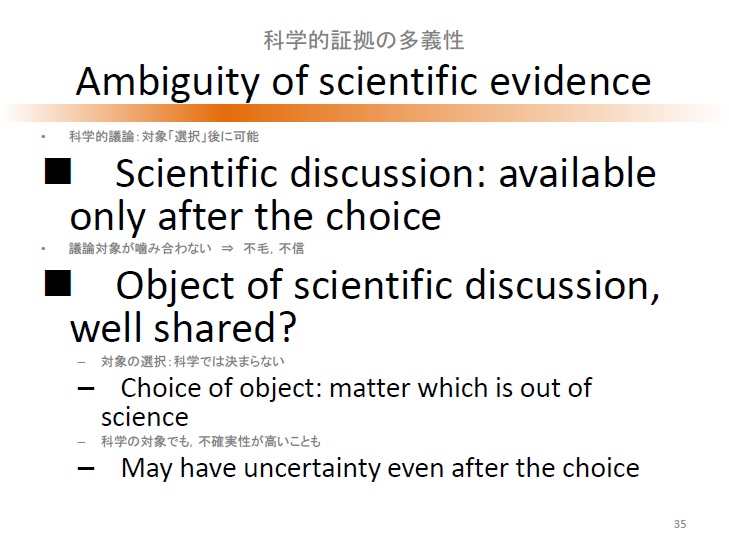

♦35

つまりこれは科学的証拠の多義性の問題ですが、先ほどお話ししたように、科学的議論というのは対象を何か一つ選択した後に、可能になるわけです。議論の対象がかみ合わないとどうなるかというと、これはもう不毛な議論になりますし、科学と社会の間で不信がますます深まっていくということになります。そして大事なことは、何を対象として選ぶか。つまり慢性影響なのか急性影響なのか、ということは、科学自身では決まらない話です。これを私たちは今日は不定性と呼んでいますが、科学自身では決まらない話なのです。それがあたかも科学で決まるように、議論されてしまうことがあります。 そして科学の対象で、対象として今度は選ばれた、慢性影響が選ばれたとしても、これは実際の不定性が、不定性がというか不確実性が高いものですから、急性影響ほどはクリアな議論は当然できないのが現状です。

To put it short, this roots from the ambiguity of scientific evidence. As I said before, we need to choose one single object in order to carry out scientific discussions. If participants in the discussion are not talking about the same things, then the discussion would become totally meaningless and the distrust between society and science would deepen. Here, the important thing is what we choose as the object of discussion. Are we going to discuss chronic effects or acute effects? This can not be decided by science. Today we call this “incertitude,” something that science cannot determine on its own. But some people discuss this problem as if it could or should be determined within the realms of science.

Then, even if chronic effect was chosen as the object of scientific discussion, chronic effects involve much uncertainty, so the discussion won’t be as clear cut as discussion for acute effects.

♦36

このような中で、私たちはどうしたらいいのかということを、最後にお話ししたいと思います。不定性の話をすると、よく伺う意見としては、不定性よりも科学的知見自体の活用をちゃんとやるべきだというふうに意見をたびたび聞かされます。しかし今まで見たように、科学的知見の活用として不定性の整理ができないと、そもそも科学で決まること、決まらないことすらちゃんと議論ができないということになってしまうわけです。

そして現状では、科学で決まらないこと、つまり規範的な判断までもが科学的なことにされることによって、逆に本来法律家であったり社会全体でやらなければいけない、社会的規範判断、つまり私たちの社会のルールとして、倫理としてどうしたらいいのかという議論が、むしろおざなりになっているように、科学者である私には見えます。つまり科学の名の下に、本来科学以外でやるべきことがおきざりになっているというのは、社会全体にとって非常に不幸なことではないかと私は思っています。当然社会的規範の判断をするというのは法律家の仕事だと私は思うのですが、そこをむしろ法律家がやらないような状況が生まれているように、私には思えます。

このような状況の中でどうするかというときには、その科学の不定性の話を、つまりどこまでが科学で決まってどこまでが科学で決まらないのか、科学的に厳密な知見とは何かということをちゃんと整理する必要があると思います。それを整理することによって、ちゃんと科学というのをより活用した制度ができていって、社会がより良いものになっていくのではないかと思っています。

Finally, I’d like to talk about what we should do in such a situation. When we bring up the issue of scientific incertitude, we often hear opinions saying that, we should focus on utilizing scientific knowledge rather than looking at the incertitude. But as we have already seen, without understanding the incertitude of science, we can not even distinguish what should be determined within science and what should be determined outside of science.

As it stands now, it seems to me that things that essentially cannot be determined by science, that is, decisions on social norms, are being left up to science. From my eyes as a scientist, though it is the duty of lawyers and the entire society to have discussions based on social norms such as the rules of our society and ethics, they do not seem to carry out the duties. I think those things that should be dealt with outside science are not being properly discussed in society and instead being imposed upon science, which is a tragedy for the whole society. Naturally, I think it is the lawyers who are supposed to make decisions on social norms, but somehow, lawyers are not doing that.

We have to think what we should do about this situation. First of all, we need to understand the incertitude of science, that is, to make clear what can be determined by science and what can not, and to define what comprises rigorous scientific knowledge. Only based on such understanding is it possible to build a system that could effectively utilize scientific knowledge, which would eventually lead to a better society.

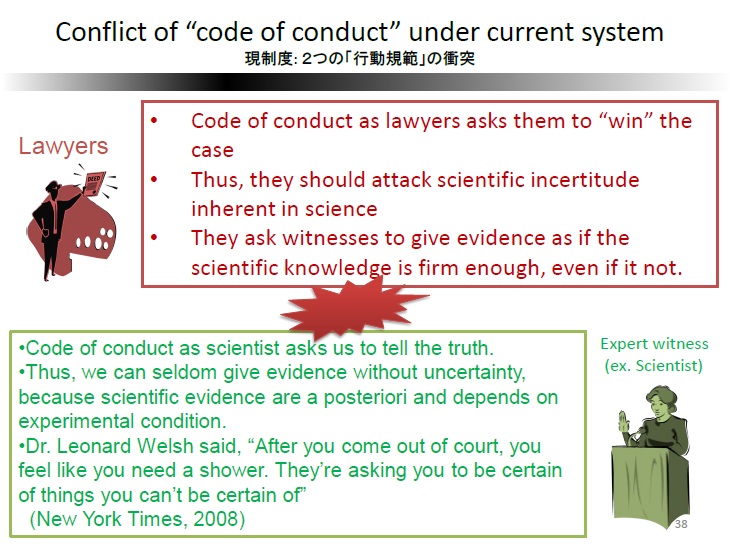

♦37-38

今までもお話ししたように、この問題は、一人一人の法律家、一人一人の科学者を「あいつはけしからん」などと言っただけではどうにもならない問題です。なぜなら行動規範というものの衝突が起こっているからです。どういうことかというと、例えば今のシステム、制度の中では、法律家というのは、クライアントといいますが依頼者の勝利のために全力を尽くさなければいけないということになっています。ですので、仮に誘導尋問をしないで、今の制度の下で、おだやかに尋問をしていたら、これは非難の対象になります。最悪の場合、懲戒請求されてしまうかもしれない。バッジが飛ぶかもしれない。ですので、ねつ造に相当することをやっているからといってその弁護士一人を責めても、これはどうにもならないのです。こういうことが起きてしまうのは、ではなぜなのかというと、これは科学の性質を少なくとも法曹界、法律界が知らないということが背景にあるわけです。もしそのような状況になっているとしたら、その責任はむしろ科学者側にもあるわけです。つまり非専門家、いわゆる法律家などに、科学とはどういうものかということを全然伝えていない、つまり科学教育というのは僕らがやっている、今日小林傳司さんもそのお話をされますが、教科書を書いているのは科学者側なのです。そういう教育を日本では全然やっていません。海外を見ると最近はやっているのです。ちょっと理科離れと言われたPISAテストなどを見ても、科学にできる話、できない話ということがテストに出るのですが、その問題になると、日本人はもう途端にできなくなります。これはもうデータで出ているのです。それが今の日本の社会です。だからそういう根本的な問題を変えていかないと、こういう問題があるということも認知されないし、制度も変わっていかないという問題があります。ですから、単に法律家が知識がないと責めるだけでは解決しなくて、科学者側にも非常に大きな責任があるということ、つまり例えていうならば、私は法廷に出て誘導尋問を受けていじめられたという意味での被害者ですが、でも一方で加害者側にもなっているという、両方の側面があるということです。

So, this is an institutional problem which cannot be overcome by individual lawyers and scientists. Accusing the conduct of individual lawyers or scientists is not going to contribute to making the situation better. It is not a conflict between individuals but between norms of conduct of the two fields. In the current system, an attorney is supposed to do whatever he/she can for the victory of his/her client. So if the attorney does not use leading questions to get desired results when he could have, then that would be criticized. At worst, he may be subject to disciplinary action, or he may even lose his attorney’s badge. It’s no use accusing lawyers personally saying that they’re fabricating facts. Those things happen not because an attorney is personally wicked or anything, but because the legal community does not sufficiently understand the nature of science. And this can largely be attributed to the responsibility of scientists. Scientists are to be blamed for not communicating to non-specialists, including lawyers, what science is. We, scientists are responsible of science education as we write the science textbooks. Professor Tadashi Kobayashi will also be talking about this subject later, too. Japanese scientific education lacks the viewpoint of teaching what science is. In foreign countries, this viewpoint is recently being incorporated in science education. Looking at the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests?the results showed Japanese students were rather disinterested in science?there is a question asking what can be studied as science and what cannot. Japanese students fall way below the standard with regard to this question. The data clearly shows it. I think that represents the Japanese society. So we have to change from the fundamental level, starting from education. Without changing the recognition of the whole society, the system won’t change. It’s not simply a matter of lawyers lacking scientific knowledge. We scientists too should be accused of neglecting our responsibility in communicating to society. So, from one point of view, you can say that I am a victim of the system as I was summoned to court to have a very unpleasant experience, but on the other hand, I am also an assailant being responsible of the existing system.

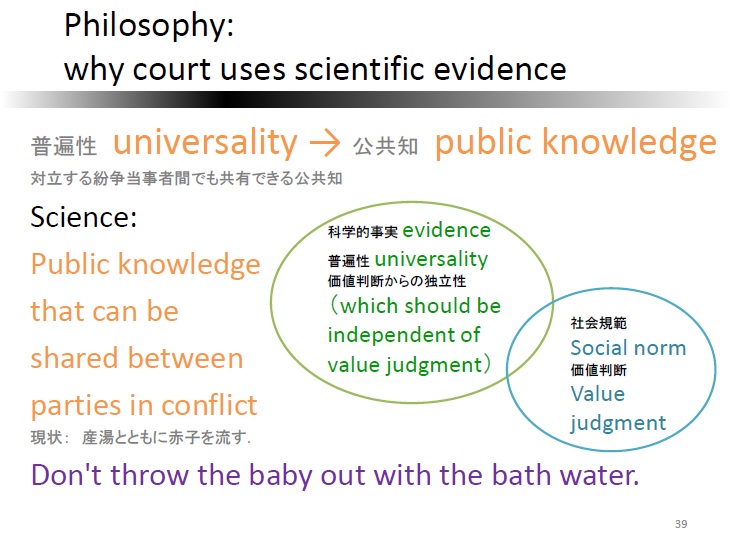

♦39

法廷が科学を用いる理由というのをもう一度振り返ると、これは対立紛争当事者間でも共有できる公共知、public knowledge、みんなでシェアできる知識であるということからやっています。つまり科学というのは価値判断からどんどん独立なものをみつけていこうという営みです。だからこそ法廷で使われるわけです。そのことが誘導尋問などの恣意的なやり方によってゆがめられてしまったらどうでしょう。これは法廷が科学を用いる大前提、一番大きな前提が壊されてしまうということになるのだと、私は思います。つまりどういうことかというと、部分的な利益や倫理よりも大きな倫理、大きな利益が破壊されている、土台が壊されていると思います。なかば、たとえていうなら、産湯とともに赤子を流すという状況になっているのが、現在の法廷での科学の現状であると、私は理解しています。

Let’s review the reasons why court uses scientific evidence. Scientific evidence is adopted in court as public knowledge that can be shared between parties in conflict. Science is an attempt to find truths independent from value judgment, and that’s why it is used in court. But what if this principle of independence from value judgment is distorted through leading questions and other arbitrary techniques? Then the very basic premise of using scientific evidence in court would collapse from the base. The more important ethics and benefits of larger society are being sacrificed for a short-viewed victory. The basis of the whole system is being destroyed. It’s like we’re “throwing the baby out with the bath water” as in the old saying. That’s my understanding of the current situations in court.

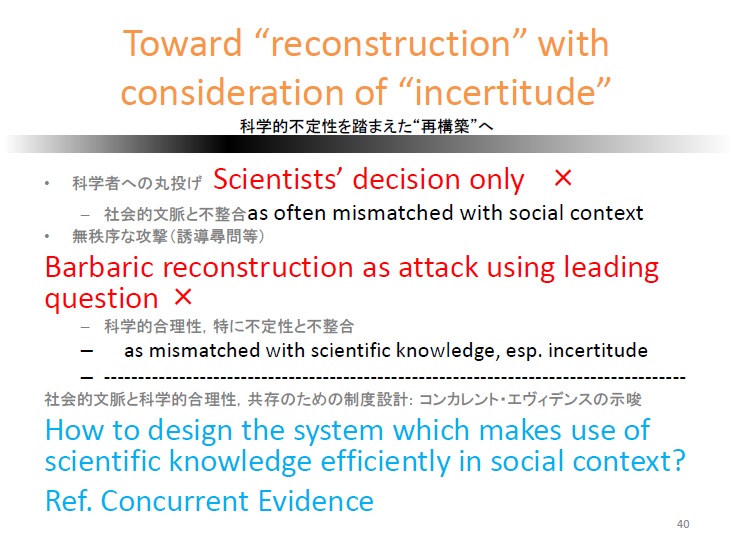

♦40

これはほとんど最後のスライドですが、今日今お話ししたことを踏まえて、制度を作り替えなければいけないと私たちは思っています。そのためにこのシンポジウムを開いているわけです。科学と社会の意思決定を考えるときには、今見たように、科学者に丸投げしてもしようがないわけです。どこで証明がなされるという基準はありません。一方で、先ほどの誘導尋問のような無秩序な攻撃をしても、これもまた不毛です。つまり科学者に丸投げしていけないからといって、では法律家がむちゃくちゃやっていいかというと、もちろんそうではありません。どちらもダメなのです。ですから第3の道を探さなければいけません。それは社会的文脈、社会の中での科学と、科学的な合理性、より正しいもの、というものが共存するような制度設計をしなければいけないということです。それを考える際には、コンカレントエヴィデンスというものが非常に参考になると私は思っています。そういうことで皆さんが今日の講演を聞いていただければと思います。

We’re approaching the final slides now. We believe that we need to reconstruct the system in light of what I have been talking about, scientific incertitude. After all, that’s why this symposium is held today. When thinking about decision making by science and society, it’s no good to just leave everything up to the scientists to decide. There is no defined or commonly shared threshold for deciding if a phenomenon has been proved or not On the other hand, it’s really meaningless to attack scientific knowledge in such a deregulated manner as leading questions. In other words, leaving all decisions up to scientists or lawyers doing whatever they please are both wrong. So, we have to look for a third way. We must design a system in which scientific knowledge can be efficiently utilized in social context, a system in which social context and scientific rationality can coexist. I believe that the concept of concurrent evidence will be of great reference in that effort. I hope you will all listen to today’s presentations with this in mind, in the context of rebuilding the existing system.

♦41-43

私個人の講演は終わりで、ここからは主催者からのお願いです。今日は議論が発散、どうしても科学と法律、科学と社会というと、議論が非常に発散する可能性があって、かみ合わなくなってくる可能性があるので、少しテーマを絞りたいと思います。それは、今日考えるのは、評価するものとしての科学です。例えば医療過誤などで医師が訴えられる、被告人になるなどということがありますが、今日はそこは考えません。むしろ科学者証人としてアセスメントをする、評価をするという場面を考えましょう。つまり当事者ではなく、第三者としての立場で科学が使われるという場面です。それからメーンに考えたいことは、事後的なレトロスペクティブではなく、これから先どうやって社会を設計していくか、そのために科学の予測を使うという場面を考えたいということです。

これは最後の制約ですが、今日はパネルディスカッションに2時間半、長い時間をとっています。そのときのやり方ですが、まずこの質問、講演も含めて、ここの講演では、申し訳ありませんが、質問はお受けしません。その代わり皆さんのお手元に質問表が配られているはずです。その質問表に、疑問な点などがあれば、まず書いてください。それを14時45分までに書いていただいて、集めます。これを私たちの方で集計して、それをもとにパネルディスカッションの中で、個々の演者が回答するということを先にやります。その後にパネルディスカッションでパネリストの間で議論をし、そのあとにフロアから、問題解決への提案をいただきます。何回もお話ししているように、「あいつはけしからん」などという話を今日はしません。そうではなく、どうしたらより良い社会が、制度設計ができるのかという点に、論点を絞りますので、フロアからのご意見も、そのようなものでお願いいたします。そして最後にまとめをして終えるということです。18時に終わりますが、その後アフターカフェというものがあり、そのアフターカフェの中で、十分にインタラクティブに、相互的に、議論ができなかった分について、より少ない人数の中で密な議論ができたらと思っております。今日は長い1日になりますが、よろしくお願いいたします。私の講演はこれで終わりです。

So that’s it with my presentation. From here are some requests from the organizer. Today, since the theme covers both science and law, or science and society, the discussion may tend to be diffusive and lose focus. So we’d like to narrow down the subject a little. Science we take up today is science as a tool for assessment. In some cases, a scientist may become the defendant, like a physician being accused of medical malpractice, but let’s omit cases like that from today’s discussions. Today, we’ll think of cases when a scientist participates in court as an expert witness to assess or evaluate something, so the scientist is neither of the accusing or defending party but provides a third party viewpoint. Another important thing is that the main themes we want consider today are not retrospective but prospective issues like how we should design the future society and how scientific predictions can be used to that end.

Our last request is about the question and answer session. Today, we have allocated quite a long time, two and a half hours for the panel discussion. So, I’m sorry about this, but we won’t accept questions after each presentation. Instead, if you have any questions, please write it down on the questionnaire that you have at hand. Please submit those questions by 14:45. We will summarize those questions and the speakers will answer the questions at the beginning of the panel discussion session. After that, there will be some discussion between the panelists, and then we will invite proposals for solution from the floor. As I have repeatedly said, we won’t be accusing anyone’s personal conducts today. That’s not the purpose of this symposium. The focus is on how to design a better system to build a better society. We hope to hear active proposals from the floor on that point. Finally we will summarize the discussions and close by 18:00. We are planning to have a more informal gathering called “Young Socrates Cafe” after the closing of the symposium to interactively discuss matters of interest in a more intimate atmosphere. This is going to be a long day for us. I hope it turns out to be productive for everyone. Thank you for your attention.

▲to page top

▲to page top